GUEST BLOG

As a consultant, I review internal audit departments at multiple financial services organizations each year while conducting Quality Assurance Reviews. While my goal for these reviews is to help the internal audit become more efficient and effective, I also focus on providing reasonable assurance that the departments are following the Institute of Internal Auditors’ International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing, which provide guidance for how to run an audit shop.

In many recent reviews, I’ve noticed an increase in the number of financial institutions that don’t fully understand the difference between internal audit and quality control. As an internal auditor, it’s essential to understand the differences between these two essential functions and ensure that they are separated appropriately. While the two terms are sometimes erroneously used interchangeably, they have significant differences that can impact roles in the organization.

What Is Internal Audit, Exactly?

Let’s start by clearly defining Internal Audit. The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) defines internal audit as “an independent, objective assurance and consulting activity designed to add value and improve an organization’s operations. It helps an organization accomplish its objectives by bringing a systematic, disciplined approach to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of risk management, control, and governance processes.”

Internal audit involves evaluating and testing an organization’s financial, operational, and compliance risks and controls. Internal auditors provide recommendations to management for corrective action to improve the organization’s performance. The scope of internal audit covers all aspects of the organization’s operations, including financial reporting, information technology, human resources, and operations.

The department ideally reports to the audit committee from a functional standpoint and a member of senior management, typically the CEO, from an administrative perspective. Its main objective is to provide reasonable assurance that the organization’s controls are effective and risks are appropriately managed.

Quality Control Is not Internal Audit!

In contrast, quality control is a function that monitors, inspects, and proposes measures to correct the organization’s products, processes, and services to meet established quality standards set by management. Quality control is a continuous and ongoing process that involves monitoring and evaluating the organization’s performance against these established quality standards. There may be daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, or even annual quality control checks of different functions and processes.

The process of performing quality control involves identifying deficient areas and implementing corrective action to address any inadequacies. Quality control can be performed by a designated department that reports to management or by the employees of a specific unit themselves. There is no independence or objectivity requirement here. For example, a branch at a credit union may have a daily report of new accounts and loans which the employees look over to make sure all documents have been obtained and all required fields have been filled out.

Quality control is essential for enhancing customer satisfaction, improving employee engagement, and reducing costs associated with poor quality and errors. When you really think about it, it would be almost impossible for any company to keep the lights on and the doors open without quality control processes in place.

The Three Lines Model

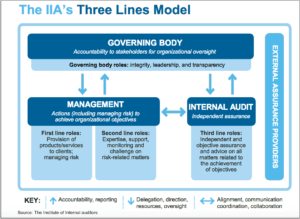

To fully appreciate the importance of the separation between these two functions, one must truly understand the Three Lines model. The 3L model is a risk management framework that outlines the roles and responsibilities of different groups within an organization in managing and mitigating risks. In addition to the model being widely accepted across thousands of organizations, the IIA updated the model, formerly known as the Three Lines of Defense, in July 2020 to better outline its structure and identify responsibilities of management, internal audit, and overall governance. The model consists of three lines, each with a distinct role and responsibility in managing risk.

The first line of defense is responsible for managing risks on a day-to-day basis. This includes the provisions set in place for products, processes, and services. Front-line employees who directly deal with customers—and other operational staff who are responsible for ensuring that risks are identified, assessed, and managed appropriately—play a large part in the first line of defense. The first line of defense is a function of management.

The first line of defense is responsible for managing risks on a day-to-day basis. This includes the provisions set in place for products, processes, and services. Front-line employees who directly deal with customers—and other operational staff who are responsible for ensuring that risks are identified, assessed, and managed appropriately—play a large part in the first line of defense. The first line of defense is a function of management.

The second line of defense is responsible for providing monitoring oversight and challenge to the first line of defense on risk-related matters. This includes functions such as risk management, compliance, and our friends in quality control. The second line of defense ensures that risks are managed consistently across the organization and that controls are in place to mitigate those risks. The second line of defense is also a function of management.

The third line of defense is responsible for providing independent and objective assurance on the effectiveness of the organization’s risk management and control processes. The third line of defense is a function of internal audit, which provides an independent and objective assessment of the organization’s risk management practices. External auditors and consultants performing outsourcing and co-sourcing engagements would also be considered part of the third line of defense.

By implementing the Three Lines model, organizations can achieve a more effective and efficient risk management framework. It enables clear separation of duties, provides a structured approach to managing risk, and ensures that there is independent assurance on the effectiveness of risk management and control processes. Ultimately, the model helps organizations to achieve their objectives while mitigating risks effectively.

Blurred Lines

Internal auditors may often feel like it is their responsibility to complete some quality control activities because no one else at the organization covers it, or management has requested internal audit to review reports or processes. As we have learned already, these duties are not the responsibility of internal audit and can cause conflicts of interest if internal audit completes them.

One problem that can arise is when internal audit does not include quality control in its annual risk assessment and audit plan, either because it slips through the cracks or because internal audit is performing the quality control duties themselves. According to the IIA Standards, it is essential for internal audit to review all areas of management’s risk management process, including quality control.

Another complication I’ve run across is when internal audit does not realize or explicitly identify that it is completing quality-control duties. Some common examples include reviewing the following reports on an ongoing basis:

- Continuous monitoring on dormant accounts

- Address file maintenance reviews

- Rate file maintenance report

- Negative balance reports

- Various exception reports

Reviewing these reports as part of a formal audit is not considered quality control. However, daily or weekly monitoring of these reports could be considered quality control and could greatly reduce the time audit has to spend on higher risk items as identified in their risk-based audit plan.

As an internal auditor for a financial institution, it’s crucial to understand the differences between internal audit and quality control and ensure that the two are clearly separated. Are you responsible for any quality control functions at your company? Leave a comment and tell us about it. ![]()

John Kaneklides is co-founder of The Audit Library, a digital collection of internal audit documents, templates, and tools, as well as a provider of audit consulting services. He is also an internal audit consultant and a former audit senior at a credit union.

This article touches on a matter that is generating a lot of controversy in my country-pre-audit. There are internal auditors that simply cannot fathom why internal auditors should not be performing pre-audits. I believe the article addresses that; at best pre-audit is a quality assurance issue that should be perform outside the third line of defense. I don’t know how widespread the controversy is in other countries; if it is it might be appropriate for IIA Global to issue a practice guide on it.