(Continued from page one) improvement and risk reduction is the peer review process. In high-volume operations such as NOCs (network operations centers) or SOCs (security operations centers), 100 percent code review processes are not a guarantee for catching all mistakes. Code can be posted to an incorrect account as easily as emails containing sensitive information can be sent to the wrong customer—even with multiple pairs of eyes reviewing it. The danger is not the technology, but humans interacting with technology in a very complex process.

Sure, some tech-based processes and operations, including cybersecurity, are complex and no one is suggesting oversimplifying them. But they don’t have to be needlessly complex. In fact, built-in complexity can make systems less secure, rather than more secure, since the mistakes are likely to happen where employees are interacting with systems they don’t fully understand. These tech-based processes should be constantly reviewed with an eye towards eliminating unnecessary steps or simplifying those that have become overwrought. If redundancy is required, there should be a sound case for it and not redundancy just to have it.

In his book, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, author Atul Gawande states: “In a complex environment, experts are up against two main difficulties: One, the fallibility of human memory and attention for mundane, routine matters. And two, people can easily lull themselves into skipping steps even when they remember them. This has never been a problem before, people say. Until one day it is.” Does this sound familiar?

Measure for Measure

Most processes that I’ve reviewed over the last 15 years measure one component of their operation very well, while ignoring other critical metrics. In the case of SOCs or NOCs, this means that the focus is on Attacks Successfully Mitigated or similar types of metrics. While those types of metrics can be important and should continue to be measured, the goal of metrics is to help surface as many operational problems so that they can be resolved. When beginning process improvement in a SOC or NOC, it is difficult to figure out specifically where problems are and what to solve. Starting with an effective measurement system helps to surface issues that people can identify immediately and then “own” through resolution. In a cybersecurity environment, the challenge is to “level the playing field” with transactions in a way that measures each team equally.

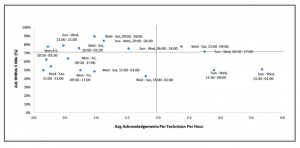

Productivity, for example, is a useful metric in a SOC or NOC environment, but isn’t usually measured or measured effectively. As an example, the scatter plot chart shown below was used to measure a “Tier 1” alert triage process in a global SOC operation. The teams were responsible for responding to all email alerts, handoffs from other departments, and inbound phone calls. Productivity had never been managed in any of the SOC operations prior to this, nor were managers aware of how to do this. Prior to implementing this metric, we grounded everyone within the triage process with the process maps to make sure that everyone was on the same page with what would be documented.

This approach was impactful as it took the “people” out of the metric and gave management and the teams a way to think about why their processes were or weren’t performing to the level they should be at. Everyone agreed that speed was a critical factor to measure and that they needed to perform better. But it did another thing that neither an audit nor any other process map could do: it changed people’s perceptions about their process and encouraged them to begin surfacing operational problems.

The teams within the process began to complain about the challenges they had in completing their jobs, both technical and process related. Those complaints surfaced problems that could be fixed or bumps that could be ironed out—exactly what we were looking for. This translated directly into risk reduction as the entire department began to focus on improving the process. The most ironic part of the feedback that we received was that most problems focused on processes and the interaction with technology rather than the technology itself.

Problems such as how runbooks were structured, multiple issues with handoffs, and even issues with the use of UTC vs. Standard Time were identified. The number of issues the teams reported were eye opening. These are the little problems that slow transactions down and increase the likelihood of something going wrong. The end result? A 25 percent increase in productivity within three months. Imagine if that type of thinking were transferred into other parts of a cybersecurity organization? A lot of risk could be managed better or reduced.

Metrics like productivity are powerful motivators when management and people in the process can see how their efforts are reflected. This is where basic process improvement tools such as standardization of processes are useful to implement. Standardizing processes is more than just ensuring there is a repeatable process, although that is where people usual start and finish. Process standardization also serves to help people within the process identify when something isn’t right, so they can correct it before the transaction enters the process. Other benefits of standardization are that transactional flow and inter-process communication are improved as well. As Gawande states in his book, “If you miss just one key thing, you might as well not have made the effort at all.”

It’s true that internal audit teams can only focus on smaller, but critical, portions of the enterprise at any given time to identify and ensure risk in its many forms is reduced or managed more effectively. Aligning with a process improvement or continuous improvement organization, however, is a way to ensure that more eyes are focused on streamlining those processes and reducing risk. In the end, the process owners, employees, managers, customers, and ultimately shareholders, will all be better off. ![]()

Mark Abrams (mark@