As the third line within the “Three Lines of Defense” governance model, internal audit must provide assurance over the effectiveness and efficiency of operations, reliability of financial reporting, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. Yet internal audit’s obligations don’t end there. The third-line responsibility also includes the mission to fight fraud, since internal audit is an essential component of an effective anti-fraud management system (AFMS). Therefore, the added value of internal audit is manifold and includes the fraud-fighting potential of internal auditors, too, especially in light of the present COVID-19-pandemic which has increased the risk of fraud.

Just how effective internal audit is at combating fraud inevitably varies, of course, from organization to organization. Yet a biennial report issued by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) provides some important insights into the role of internal audit in anti-fraud activities and the effectiveness of the function as a whole in identifying and deterring fraud.

In the latest edition of its study on fraud, “Report to the Nations: 2020 Global Study on Occupational Fraud and Abuse” the ACFE has gathered data on 2,504 fraud cases from 125 countries with total losses of more than $3.6 billion. With its statistical and empirical power, the “Fraud Report,” as it is known, has become the most widely quoted source of occupational fraud data in the world. Because of these in-depth fraud and control details summarized since 1996, the Fraud Report has also become a major source of fraud information for internal audit in order to strengthen its own position as the third line of defense within corporate governance. The report also opens empirical room to critically question whether internal auditing really provides added value to the organization on anti-fraud and the effectiveness of the function as required by professional standards.

Before we wade into the data, let’s take a moment to consider where the responsibility to look for fraud is rooted in the role and duties of internal audit. The theoretical foundation for the implementation of an internal auditing function is the existence of the discrepancy between legal property and the factual use of property by management, from which the widely researched principal-agent conflict resulted. In order to overcome—or at least to reduce—that conflict, internal audit should operate, as stated by the Institute of Internal Auditors’ International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing, as an “independent, objective assurance and consulting activity designed to add value and improve an organization’s operations. It helps an organization accomplish its objectives by bringing a systematic, disciplined approach to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of risk management, control, and governance processes.” It would be difficult to embody that statement without some effort to consider the potential for fraud in the organization, assess anti-fraud controls, and to play a role in deterring it from occurring and escalating instances where it is suspected.

‘Steady Improvement’

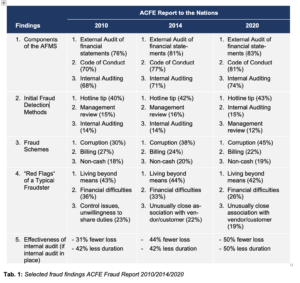

Indeed, according to the 2020 Fraud Report the internal audit function has made some progress in this fraud-fighting role. The ACFE study notes that the effectiveness of internal audit in combating fraud has steadily improved. As displayed in Table 1 (below), when internal audit as an anti-fraud control was in place, for example, the average loss reduction per fraud case increased from 31 percent to 50 percent, whereas the average duration per fraud case declined from 14 to 12 months, compared to 24 months when internal audit was not in place as an anti-fraud control.

Other data points also highlight the gains internal audit has made in anti-fraud programs. Within the ranking of initial fraud detection methods, the internal audit function climbed from third (initially detecting 14 percent of examined fraud cases in 2010) to second in 2016, behind whistleblower hotlines. It held second place in 2018 as well as in the 2020 report. Furthermore, the presence of internal audit as a top-three component within the AFMS increased from 68 percent to 74 percent.

Some other notable finding of the 2020 ACFE Fraud Report include:

- The occurrence of corruption soared globally from 30 percent to 45 percent in 2020, and in some regions it grew even dramatically higher. In Southern Asia, for example, it rose from 62 percent to 76 percent in 2020.

- The top three reported fraud schemes remained the same: corruption, billing, and non-cash.

- The typical profile of a fraudster stayed the same: a 40-year-old male with a university degree, never charged or convicted for fraud before, and never punished or dismissed by his employer. He has been working for his boss for about three years, behaving inconspicuously, but privately has been living beyond his means and falling into financial difficulties.

Not All Good News

Although the effectiveness of the internal audit function on anti-fraud measures has generally increased, one still has to critically challenge this deduction from the above statistics. Based on the following questions, the general effectiveness of internal audit can be seen in a different light:

- The presence of the internal audit function as a top-three component within the AFMS increased from 68 percent to 74 percent, significantly higher than the tip or whistleblower hotline (64 percent). But as an initial source of fraud detection the hotline is much more effective (43 percent) than internal audit (15 percent). Why was a hotline three times more effective as an anti-fraud control than internal audit?

- The probability of detection by internal audit can be roughly calculated as follows (figures for 2020): Of all 2,504 fraud cases, 74 percent (1,853) involved the presence of internal audit. At a 15 percent detection source, internal audit would have detected 376 cases, which gives 20.3 percent of all 1,853 cases where internal audit was present. In other words, internal audit detected every fifth fraud case. Why didn’t internal audit detect more than just one-in-five fraud cases?

- “Lack of internal controls” (32 percent) and the “override of existing internal controls” (18 percent) were the primary internal control weaknesses in the 2020 Fraud Report and also in the reports before. Another study (PwC, 2018, Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey) reported a corresponding finding that the “opportunity” to commit fraud as one precondition of the “fraud triangle.” So, the misuse of existing internal control weaknesses was the most influential factor contributing to fraud by 59 percent. Why did the internal audit function oversee the weaknesses of the internal control system that it was responsible for assessing over the years?

- The expectations of management and other stakeholders towards internal audit with regard to its anti-fraud potential is frighteningly low. An IIA study last year, “Defining, Measuring, and Communicating the Value of Internal Audit—Best Practices for the Profession,” bears this out. Among 15 tasks of internal audit with the largest potential to add value, respondents ranked “investigating fraud” 12th and “assessing fraud risks and deterring fraud” 14th. Other empirical studies suggest similar opinions. Why is the perception of management and stakeholders regarding the anti-fraud-potential of internal auditing so reserved?

- In the face of certain efforts of qualification and improvement of internal audit, one can also reflect whether other factors, such as organizational ones, could also be hindering internal audit in performing better on its anti-fraud duties. The question is: Could there be organizational reasons outside the internal audit function why internal auditing underperforms in this area?

Summarizing the ambivalent picture, empirical data indicate that the internal audit function supplies certain anti-fraud-success. But, the anti-fraud results of the internal audit function are less than should be expected, considering all the efforts and costs allocated to the function. Additionally, fraud risk is simultaneously on the rise. According to the latest ACFE-survey (“Fraud in the Wake of COVID-19”), 79 percent of respondents have seen an increase in the overall level of fraud since the onset of the pandemic, and 90 percent expect this critical trend to continue well into 2021.

Internal Audit’s Anti-Fraud To-Do List

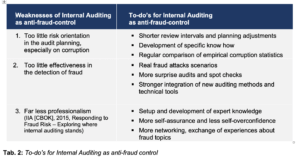

It’s likely that many internal auditors perceive the increasing pressure to more effectively combat fraud and that there is some work to be done to get back on track. In Table 2 the identified current weaknesses of the internal audit function are contrasted with possible “to-do’s” in order to increase the effectiveness of internal auditing as an anti-fraud control.

Additionally, internal audit should further strengthen its own organizational independence. This follows an interesting explanatory approach which was deduced from the “fraud evasion triangle,” whereby three groups favor fraud: crafty perpetrators, dependent internal auditors, and nonbinding external auditors (Ergin/Erturan, 2019, Fraud Evasion Triangle: Why Can Fraud Not Be Detected?). Following that model, the disciplinary and financial dependency of internal audit on top management was identified as one major weakness in gaining more anti-fraud success.

Discussion of the To-Do’s

Getting started on improving internal audit as a fraud-fighting function and tackling these “to-dos” can be daunting. Yet there are small (and not so small) steps that can be taken to advance internal audit on the anti-fraud maturity scale.

The risk orientation within the audit planning process could be strengthened by shortening the review intervals of certain fraud-prone issues, such as fake invoices, fictitious employees, or wrong accounting entries. The audit frequency should then strictly follow the specific fraud risk of the internal process and therefore also lead to adjustments of the audit planning process. The absence of specific know-how of corruption auditing is a significant weakness of internal auditors which should be addressed with appropriate qualification measures and added training.

Another “to-do” is the critical and regular engagement with the latest empirical corruption statistics by country, industry, company size, and other data points. These data are often available for free with a little internet searching on sites such as ACFE, IIA, policing agencies, regulators, international accountancy firms, and others.

The effectiveness of fraud detection by internal audit could be increased by more realistic fraud attacks for testing purposes (penetration testing) and “white hat” attacks to test the possibility of circumventing the internal control system. The leading question is not whether the company complies with a rule, but how a fraudster could misuse the rule to gain from it. More (possibly all) internal audits in this area should be carried out on a surprise basis to assess conditions as they are. Additionally, new auditing methods and technical tools such as mass data analysis software or artificial intelligence tools should become integrated in the internal audit function.

More professionalism means internal audit teams need more expert knowledge in the internal audit function. Space for improvement is more than obvious: Only 6 percent of internal auditors possess anti-fraud-certificates such as the Certified Fraud Examiner certification, whereas know-how in audit psychology, soft skills, and forensic techniques is often lacking. Internal auditors should run through more self-assurance processes by internal or external quality assessors in order to adjust the potential for overconfidence among internal auditors: 60 percent of all internal auditors believe they have good anti-fraud-knowledge or even describe themselves as “anti-fraud experts!” More professionalism could also result from more networking, including a frequent exchange of experiences about fraud topics by interdisciplinary, interbranch working groups at organizations such as IIA chapters, ACFE, ISACA, and others.

The organizational independence of internal auditors could be strengthened by the filling of leadership positions (at least the head of the internal audit department) with greater input and oversight from the audit committee. Frequent job rotation (at least once in five years) and a high degree of internal autonomy with (almost) unlimited access to corporate data can also help improve independence and objectivity. Avoiding the use of internal audit as a so called “management training ground” for young professionals should also be considered here, since the temporary responsibility as internal auditor could bring pressure and bias to young auditors when auditing the department of their next desired career step after leaving internal auditing.

Looking Ahead

As in the past, the ACFE again delivers numerous worldwide empirical data of occupational fraud with its 2020 Fraud Report, which should be of great interest for shareholders, managers, compliance officers, other stakeholders, and—last but not least—chief audit executives. Based upon the results from the current Fraud Report, several areas of conflict can be identified, bringing the internal audit function under significant compulsion to act:

- Internal Auditing brings a measurable anti-fraud contribution, but this value is rarely acknowledged by management and stakeholders.

- Existing deficiencies of internal controls advantage the majority of all fraud cases. Because internal auditing is mainly responsible for assessing the system of internal controls, the function has to handle the criticism for weak internal controls due to myopia or even blindness.

- A substantial development and quality improvement of the internal audit function between 2010 and 2020 was almost invisible. This could lead to unfavorable decisions by management, such as cost or staff reductions, especially during difficult times as the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Radical changes will likely be necessary to improve the effectiveness of internal audit in anti-fraud efforts. These changes include a highly professional internal audit function with a very sensitive anti-fraud risk radar in a rather independent organizational environment. Only then will the internal audit function be in the position to unfold its anti-fraud potential, creating added value as stipulated in the international professional standards of internal auditing. ![]()

Hans-Ulrich Westhausen, PhD, CIA, CCSA, CFSA, is head of Group Auditing and Compliance Officer for ANWR GROUP in Mainhausen / Duesseldorf, Germany.