Many internal audit shops include a rating or grade at the end of an audit report intended to summarize the findings and bring attention to the most important conclusions of the report.

Ratings may be scored with a number—from one to five, for example; a color—often red, yellow, and green; with an adjective such as “satisfactory,” “needs improvement,” or “unsatisfactory”; with a letter grade from “A” down to “F”; or with other mechanisms.

While boards and senior management tend to love the audit report ratings, since they quickly guide their focus to what needs the most immediate attention, process owners and auditees tend to hate them. They think that boiling the findings down to one letter or color oversimplifies the issues and can paint their units in an unfair light.

The tension leaves chief audit executives stuck in the middle. They can include ratings and battle their audit clients when they push back over the audit report summary ratings, which can often result in a prolonged back and forth. Or they can omit them and answer to senior executives and board members who don’t appreciate wading through long paragraphs to find the summarized results of the audit.

“Ratings can be a powerful tool, but if management and the audit committee place undue emphasis on them, they tend to have a polarizing effect on line and operating managers whose performance ends up being summarized in a single word: ‘unsatisfactory,’” wrote Institute of Internal Auditors President and CEO Richard Chambers, in a blog post on the topic.

Growing in Popularity

To be sure, the practice of including rating in audit reports appears to growing in popularity. A survey by the IIA found that about two-thirds of internal auditor respondents said their organizations include some type of rating in their audit reports.

“I do see more visuals,” says Audrey Gramling, chair of the school of accounting at Oklahoma State University. She says they make it easier for readers to quickly identify areas of risk. In doing so, ratings help mitigate one of the more common criticisms of audit reports—namely, their length.

Ratings also can help in quickly comparing one area, location, or branch to another, says Brendan Friedman, director of internal audit at Mobile Mini, a provider of portable storage solutions, which includes ratings on audit reports. Members of the audit team assess each of the company’s approximately 136 locations on a regular basis and assign each one a score based on a series of criteria.

Audits at Mobile Mini are scored from zero to five in increments of .1, Friedman says. The goal is for each branch to score of at least a four, or green. Scores between three and four are yellow, and below three is red. The calculations are weighted, so the ratings quickly focus attention on more critical areas, such any lapse in safety protocols.

Creating a Battleground

Despite their benefits, ratings can provoke disagreements. Few managers, not surprisingly, want to see their areas earn an unsatisfactory rating. That’s especially true when the ratings will be seen by upper management and could impact their performance reviews or compensation. “It’s human nature that people get entangled into how a third party, the internal auditor, is projecting the unit head to senior management,” says Parveen Gupta, professor of accounting at Lehigh University.

“Ratings can be a powerful tool, but if management and the audit committee place undue emphasis on them, they tend to have a polarizing effect on line and operating managers whose performance ends up being summarized in a single word: ‘unsatisfactory'”

—Richard Chambers, President and CEO, Institute of Internal Auditors

Disagreements about ratings can consume time and energy that would be better spent identifying ways to remediate control weaknesses. Some chief audit executives report feuds over ratings that can go on for weeks and months. Line managers may agree with all of the findings of the audit as they are summarized in text, but then push back on the summary rating. They also can damage any goodwill established between auditors and auditees, and promote distrust among both parties.

Using Ratings Effectively

Internal auditors can take steps to leverage the benefits of ratings while minimizing their shortcomings. Before implementing a rating system, the organization should have a fairly mature governance and risk management structure, says Joseph Mauriello, director of Center for Internal Auditing Excellence at the University of Texas at Dallas. This requires a common risk language with which auditors and auditees can discuss observations. “If you don’t have a shared risk language, it takes away from the ability to communicate,” the nuances of rating, he adds.

Without a common language, it becomes difficult to reach agreement on the severity of each risk, Mauriello says. Management might argue that a risk the auditor deemed high is actually low, but they’re not referring to the same metric. For instance, the audit might reveal business purchases that weren’t pre-approved—although not fraud, a violation of company policy. Absent a common audit and control framework, a manager may not recognize the potential exposure, nor the risk that any circumventions of the control environment will escalate.

One way to establish a common framework is through workshops focused on discussions around control and enterprise risk management, Mauriello says. The audit team and managers can discuss threats and risks and come to a shared understanding of them. “The interaction makes it easier when you’re doing an audit (to show) the common framework,” he adds.

Be Objective

Another starting point is making the audit criteria as objective and clear as possible. Just as students need to know how they’ll be graded, managers should understand the methodologies used by internal auditors evaluating their departments, Gramling says.

Allowing management to provide input at the initial stages of developing new audit methodologies criteria helps in fostering understanding. Erica McManaman is chief auditor and senior vice president with Signature Bank in New York. When Signature Bank’s Audit department was revamping its audit report ratings, McManaman and her team discussed with senior management the approach and specific criteria that would be considered when assigning ratings to individual audit reports. “As a result of this effort, management has a better understanding of and appreciation for the justification for assigning a particular rating,” she says.

Signature Bank’s audit reports include ratings for individual issues, as well as an overall report rating. The overall report rating is determined by various factors, including the number of high, moderate, and low risk issues identified, and the number and type of regulatory findings. “Our audits generally consist of a front-to- back review of the business or function, thereby giving the reader a full picture of how the business or function is controlled,” she says.

“Because the ratings focus on a specific audit issue, rather than for an area as a whole, management is less likely to be defensive.”

—Barbara Jena, chief audit officer at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio

McManaman and her team include an explanation of the drivers behind the rating. For instance, if it’s a new line of business, perhaps the implementation of the system infrastructure has been delayed, resulting in control deficiencies. “Including the context is helpful in informing consensus and providing support for report ratings,” she says.

There is at least one hidden benefit for process owners to including a rating with audit findings: While few auditees welcome a poor score on an audit report, at times, a less than satisfactory score can help an area get the resources it needs to improve.

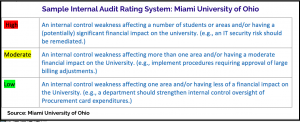

Barbara Jena, chief audit officer at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, has been rating the risk levels of specific internal audit issues for about ten years. “Because the ratings focus on a specific audit issue, rather than for an area as a whole, management is less likely to be defensive,” she says.

The ratings—high, moderate, low—are not included in audit reports, but are in an audit issue log that’s presented semi-annually to senior management and the finance and audit committee of the board. Miami University’s procedures have been recognized by The IIA for conformance with IIA’s International Standards.

While any internal audit ratings should be comprehensive, they should also be simple, Mauriello says. “The more complicated, the more folks will nitpick.” They’re apt to get lost in the details, and lose sight of the risk itself.

It also helps to tailor conversations to the auditees’ understanding of accounting and auditing principles. For instance, the managers at Mini Mobile’s branch locations have a range of responsibilities and may not be aware of the wider ramifications of their actions. So, a conversation might focus on the ways that adhering to the company’s purchasing policies helps the organization overall. “We try to help them develop action plans to improve,” Friedman says.

Very rarely, Friedman will change a rating that a manager questioned. This might occur, for instance, after obtaining input from another expert, such as a safety director. These conversations occur before the report is formally issued.

Ratings Alternatives

While the popularity of ratings shows no sign of decline, not all organizations use them. Some organizations identify issues as reportable or not reportable. While simpler than a ratings structure, this still requires some judgment by the auditor, says Warren Stippich, a partner in Grant Thornton’s Advisory Services practices

When Stippich previously held auditor roles and presented to senior management, he’d often use several sentences to summarize the reports. Although somewhat more involved than a single rating, “this could also force the quality of the conversation to be richer,” he adds.

Typically, organizations looking to focus on the substance of their overall control environment are less likely to use ratings, “They want a holistic conversation around risk,” Stippich says, “versus elephant hunting.”

Some organizations worry that ratings move auditors to a policing role, when the audit team is trying to take a more collaborative approach. And, organizations in which ratings are causing extreme contention—say, the audit report is held up for months because of a disagreement over a rating—also likely will consider moving away ratings, Stippich says. ![]()

I believe you owe it to the people you report to, the Audit Committee, to provide them with some context regarding the audit findings in each report. At a minimum each finding should be risk rated. The overall audit grade should be based on the number and risk severity of the audit findings. These risk ratings and audit grades will allow the Auditor to produce effective audit dashboard reports for their Audit Committee, helping the Committee decipher all the reports they receive each meeting.

Internal Audit observations should be factually correct and objective. The report should provide enough objective evidence to provide a view of the control environment, acceptable to the management and the Board. The use of a rating system brings in subjectivity and makes it judgemental. Stakeholders, at times, tend to focus too much on the rating and misses out on important control issues. It’s better to present facts e.g. if an auditor has tested 10 internal controls in a process, then state:

7 controls were operating effectively

2 controls, x number of deviations were observed out of a population of y (we can also state the impact)

1 control was not in place and state the impact

It’s a fair representation and stakeholders can collectively focus on sustained remediation, which make the control environment robust

Really helpful article

A big challenge with the audit report and its rating(s) is the ability of users to understand the concept of “potential for losses as a result of a weak or deficient control and the likelihood of the loss (not only actual losses which are evident). This typically requires education and dialogue with the owner of the process in the early stages of the audit. It is also important to provider a clear description of the level of risk in the finding which is expressed by the condition, criteria, cause and consequence (aka., impact). because the user of the report should be able to obtain a reasonable understanding of the issue from its description. .